Progress is slowing

1—Progress is slowing

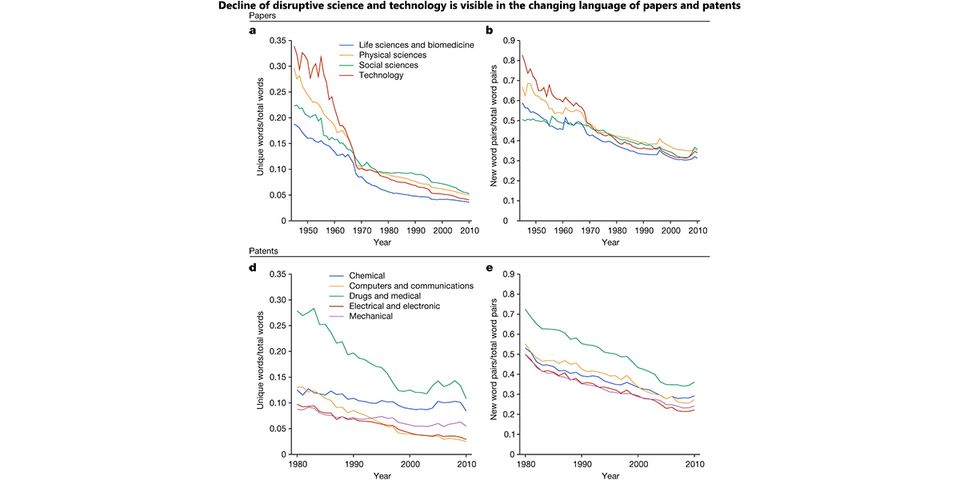

According to a new paper published in Nature, scientific research has become less innovative since the 1950s:

"Recent decades have witnessed exponential growth in the volume of new scientific and technological knowledge, thereby creating conditions that should be ripe for major advances. Yet contrary to this view, studies suggest that progress is slowing in several major fields."

The authors – Michael Park, Erin Leahey and Russell Funk – analysed 25 million papers (1945–2010) and 3.9 million US patents to measure the disruptiveness of science and technology. They found that "despite large increases in scientific productivity" – i.e. people are still publishing lots of papers and filing plenty of patents – innovative activity is slowing.

Why might that be? After ruling out several possible explanations that were inconsistent with the data, the authors suggest it could be due to the trend of:

"...scientists' and inventors' reliance on a narrower set of existing knowledge. Even though philosophers of science may be correct that the growth of knowledge is an endogenous process—wherein accumulated understanding promotes future discovery and invention—engagement with a broad range of extant knowledge is necessary for that process to play out, a requirement that appears more difficult with time. Relying on narrower slices of knowledge benefits individual careers, but not scientific progress more generally."

You can read the full paper here (~30 minute read), which offers up solutions such as having universities change their focus from quantity to quality, and giving researchers time "to read widely... to keep up with the rapidly expanding knowledge frontier", allowing them to "inoculate themselves from the publish or perish culture".

2—The demographic transition

In 1968 Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, which as you might have guessed from the title warned about global overpopulation, and began with the following grim prediction:

"The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate."

He was, of course, wildly off point:

"Meanwhile, the global fertility rate peaked in 1965 at over 5 children per woman. Since then, it has been in relentless decline — now all the way down to 2.3. While the Green Revolution was the product of innovation and thus the resulting productivity spike was legitimately unexpected, the drop in birthrates merely recapitulated at the global level a dynamic that had begun in rich countries a century earlier. Between 1870 and 1920, fertility rates fell by 30 to 50 percent in western Europe and the United States. Along with a corresponding, and generally earlier, drop-off in mortality rates, this phenomenon is known as the 'demographic transition' — the sea change from a high birth-rate, high death-rate society to one with low birth and death rates."

That's from Brink Lindsey, who recently penned an essay on the global fertility collapse – precisely the opposite of Ehrlich's fearmongering back in 1968 (thankfully Ehrlich didn't manage to get many of his forced population control "crash programs" implemented). Lindsey continued:

"Awareness of the problem remains far from widespread. I reckon more people today are still worried about the nonexistent danger of runaway population increase than share my concern about demographic stagnation and decline. To the extent people are even aware of the dramatic worldwide fall in fertility, they are more likely to see it as a lucky break that has saved us from the population bomb than as the Charybdis to overpopulation's Scylla."

You can read Lindsey's full essay here (~17 minute read).

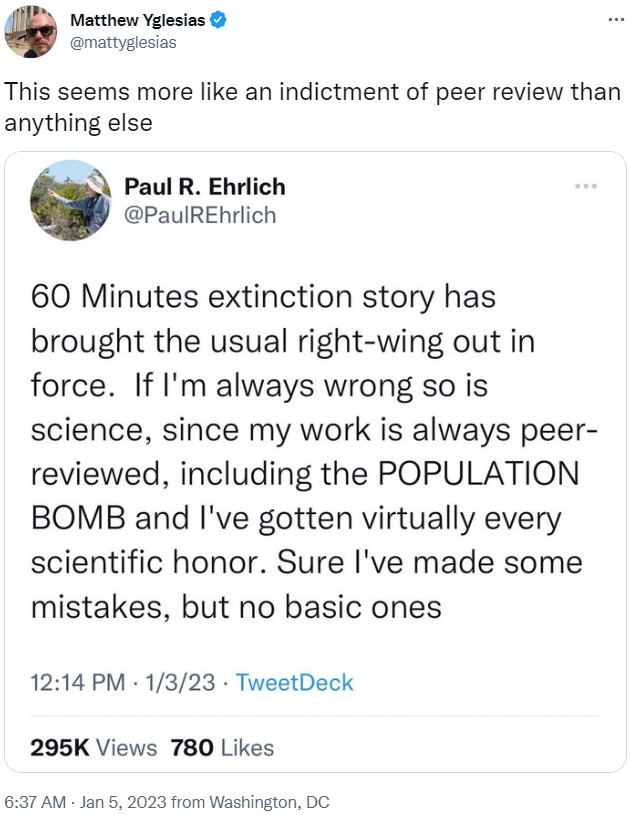

3—Invoking 'science'

4—The struggle for power

You might have heard about how the US Republican party has, at the time of writing, failed to elect a new speaker of the House after eight attempts. It was the first time since 1923 that the House had to adjourn without choosing a speaker.

The difficulty for what should be a simple task comes from a power struggle within the party itself. So writes Aden Barton:

"When John Boehner took the speaker's gavel in 2011, he led a caucus that broadly agreed on the need for dramatic deficit reduction. In contrast, Kevin McCarthy—or whoever takes the speaker's gavel—will preside over a Republican caucus that's internally divided over fiscal issues.

On the one hand are fiscal hawks who want deficit reduction to be a top Republican priority in 2023, just as it was in 2011 and 1995.

Inflation has made this narrative especially salient, as Republicans are able to blame higher prices on Democrats' fiscal irresponsibility. Danny Weiss, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation and former chief of staff to Speaker Nancy Pelosi, told me that so long as inflation stays high, Republicans have a strong incentive to focus on the deficit.

But there's also a significant faction of fiscal moderates who draw their inspiration from President Donald Trump, who vowed not to cut Social Security and Medicare during the 2016 campaign and presided over a large increase in the deficit.

'This Republican class is very different than the one elected in 2010,' Ben Ritz of the Progressive Policy Institute told me. A decade ago, Tea Party Republicans viewed cutting government spending as a top priority. In contrast, he said 'this class is all in on the Trump culture war'."

Barton has plenty more about the internal divide and struggle for power within the Republican party here (~6 minute read), including what it means for the inevitable debt-ceiling showdown that will occur sometime this year.

5—Further reading...

🍟 "Top [Chinese] officials are discussing ways to move away from costly [microchip] subsidies that have so far borne little fruit and encouraged both graft and American sanctions, people familiar with the matter said."

🧐 "[C]onsumers respond to a 1-cent increase from a 99-ending price as if it were more than a 20-cent increase."

✈️ "When private equity funds buy airports from governments, the number of airlines and routes served increases, operating income rises, and the customer experience improves."

🚚 "Amazon plans to cut more than 18,000 jobs [~1.2% of its workforce], the largest number in the firm's history."