The age of inflation

1—The age of inflation

Inflation is still running at – or close to – double digits in most advanced economies. But how did we get here, and will we ever get back to 'lowflation'? Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff recently weighed in:

"For years, many economists have assumed that inflation had been permanently tamed, thanks to the advent of independent central banks... Indeed, well into the COVID-19 pandemic, most regarded a return to the high inflation of the 1970s as implausible. Fearing a pandemic-driven recession, governments and central banks were instead preoccupied with jump-starting their economies; they discounted the inflationary risks posed by combining large-scale spending programs with sustained ultralow interest rates... Having waited too long to raise interest rates as inflation built up, central banks are scrambling to control it without tipping their economies, and indeed the world, into deep recession."

Looking forward, Rogoff warned that "the era of perpetual ultralow inflation will not come back anytime soon":

"Instead, thanks to a host of factors including deglobalisation, rising political pressures, and ongoing supply shocks such as the green energy transition, the world may very well be entering an extended period in which elevated and volatile inflation is likely to be persistent, not in the double digits but significantly above two percent."

You can read Rogoff's full article here (~24 minute read), which goes on to discuss the political pressures faced by central bankers; the failure that is modern monetary theory; the possibility of negative interest rates; and that because "stimulus spending is political", governments have been so eager to use it that there's now very little fiscal capacity left to "take large-scale actions to protect the vulnerable in the event of a deep recession or catastrophe".

2—Stocks for the long run

The world is seemingly always going to hell in a handbasket, but in the long run people still need a place where they can reliably secure durable returns. Thankfully Wharton's Jeremy Siegel recently updated his 1994 book called Stocks for the Long Run:

"It's interesting because the first edition, which came out in May 1994, used data through the end of 1992. The long-term real return (net of inflation, from investing in stocks) 1802 onward was 6.7% in real terms. I updated it till June of this year and it's 6.7% real — exactly the same as the last 30 years, despite the financial crisis, COVID, and so forth. It’s remarkably durable. We also know returns from investing in stocks are remarkably volatile in the short run. But the durability of the equity premium (or the excess return from stocks over a risk-free rate like a Treasury bond) is quite remarkable."

On the recent performance of US monetary policy, Siegel says:

"I've been calling Jay Powell's monetary policy the third worst in the 110-year history of the Fed. I may actually raise it to the second worst, but we'll see what happens. The worst, of course, is the Great Depression, where they let all the banks fail when they were actually formed to prevent exactly that from happening. When the pandemic hit and money supply exploded, I said this is going to cause inflation. You've never seen that 25% M2 money supply increase — 1870 onward, there has never been a money supply increase that fast.

I said this is just absolutely crazy. This is going to produce a tremendous amount of inflation. And it did."

Siegel notes that predicting what central bankers are going to do "amuses" him, because they have no "concept of what they're going to do in 2023. Clearly, in 2021, they had zero concept of what they were going to do this year".

Be sure to check out the full interview between Jeremy Schwartz and Jeremy Siegel here (~9 minute read).

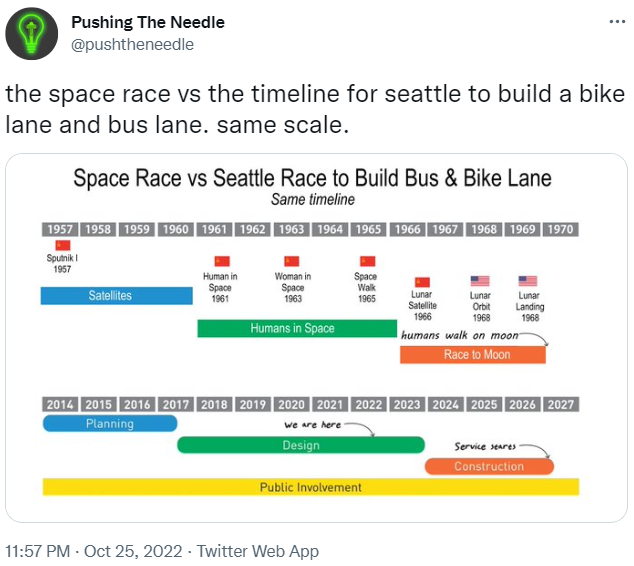

3—It shouldn't be this hard

4—An ongoing crisis

From where did COVID-19 originate? We'll probably never know but the sleuths at ProPublica, in partnership with Vanity Fair, did some investigating, noting an ongoing crisis at the Wuhan Institute of Virology [WIV] during late 2019 and various other inconsistencies in China's official narrative:

"Reading between the lines is essential to understanding what the WIV dispatches really mean. As Geremie Barmé, an emeritus professor of Chinese history at the Australian National University, who analysed key documents at our request, said of CCP communications, 'The style of self-protection, of rounding things out, of avoiding the truth, is a highly developed, bureaucratic art form.'

Without more evidence, it is impossible to know the details of what the assembled group knew and discussed that day. But at least one news report supports the notion that the virus may have been circulating at that time. In March 2020, a veteran journalist with the South China Morning Post reported that she reviewed internal Chinese government data on early cases of COVID-19 that included a 55-year-old in Hubei province, where Wuhan is located, who contracted COVID-19 on Nov. 17, 2019.

That was just two days before Ji arrived at the WIV, bearing urgent instructions from the highest levels of China's government."

The investigators also looked into the puzzling issue of how quickly the first vaccine was developed in China:

"On Feb. 24, 2020, Zhou became the first researcher in the world to apply for a patent for a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. His proposed vaccine worked by reproducing a part of the virus’s spike protein known as the receptor binding domain. In order to start vaccine development, researchers would have needed the entire SARS-CoV-2 genetic sequence, the interim report says.

...

Vanity Fair and ProPublica consulted two independent experts and one expert adviser to the interim report to get their assessment of when Zhou's research was likely to have begun. Two of the three said that he had to have started no later than November 2019, in order to complete the mouse research spelled out in his patent and subsequent papers.

...

Zhou and his colleagues described their COVID-19 vaccine research in a preprint posted on May 2, 2020. When it was published in a peer-reviewed journal three months later, Reid found, Zhou was listed as 'deceased.' The circumstances of his death have not been disclosed."

The Chinese government, as we all know, didn't officially recognise that the virus was circulating until weeks after November 2019.

You can read the full investigation here (~37 minute read), which reports "that Xi himself had been briefed on an ongoing crisis at the WIV", but that "[w]ithout the cooperation of China's government, we can't know exactly what did or didn't happen at the WIV, or what precise set of circumstances unleashed SARS-CoV-2".

5—Further reading...

🔌 The European Union banned the sale of new petrol and diesel cars from 2035.

🌞 From the NYT: "In the long run, we are likelier to make progress when we adopt partial solutions that work with the grain of human nature, not big ones that work against it. Sometimes those solutions will be legislative — at least when they nudge, rather than force, the private sector to move in the right direction. But more often they will come from the bottom up, in the form of innovations and practices tested in markets, adopted by consumers and continually refined by use. They may not be directly related to climate change but can nonetheless have a positive impact on it. And they probably won't come in the form of One Big Idea but in thousands of little ones whose cumulative impacts add up."