Collapsing into absurdity

1—Collapsing into absurdity

The term 'effective altruism' – the idea of giving to maximise benefit, with obvious utilitarian roots – has grown in popularity in recent years, with billionaires including Cari Tuna, Dustin Moskovitz and Sam Bankman-Fried pledging to give away vast amounts of their wealth to such causes.

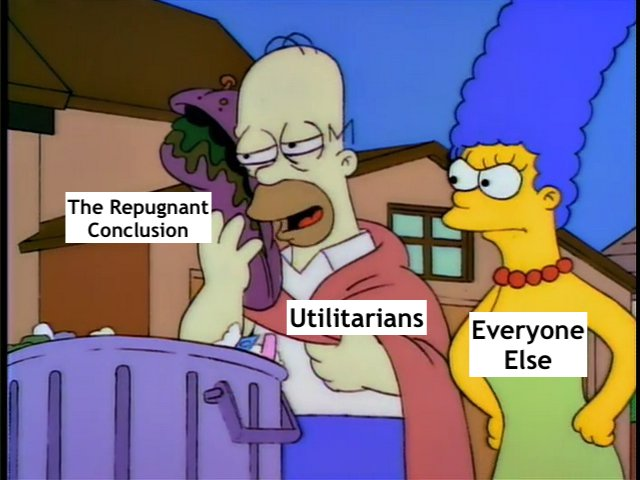

But because of its roots in utilitarianism, how can effective altruists "avoid the train to crazy town"? That's an important question recently pondered in detail by Peter McLaughlin:

"Once you allow even a little bit of utilitarianism in, the unpalatable consequences follow immediately. The train might be an express service: once the doors close behind you, you can't get off until the end of the line.

This seems like a pretty significant problem for Effective Altruists. Effective Altruists seemingly want to use a certain kind of utilitarian (or more generally consequentialist) logic for decision-making in a lot of situations; but at the same time, the Effective Altruism movement aims to be broader than pure consequentialism, encompassing a wider range of people and allowing for uncertainty about ethics. As Richard Y. Chappell has put it, they want 'utilitarianism minus the controversial bits'. Yet it's not immediately clear how the models and decision-procedures used by Effective Altruists can consistently avoid any of the problems for utilitarianism: as examples above illustrate, it's entirely possible that even the simplest utilitarian premises can lead to seriously difficult conclusions."

McLaughlin goes on to conclude that he finds "large parts of Effective Altruism appealing ('the movement has provably done a lot of good'), although I'm turned off by many other aspects". As for the theory itself, he's "not sure how it gets off the ground at all without leading to absurdities". Its core is solid but after that it becomes "murkier":

"It's definitely true in the limited realm of charitable donations, where large and identifiable differences in cost-effectiveness between different charities have been empirically validated. It becomes murkier as we move outwards from there—issues of judgment, risk/reward trade-offs, and unknown unknowns make it less obvious that we can identify and act on interventions that are hugely better than others—but it's certainly plausible. Yet, while Effective Altruism has made a prominent and potentially convincing case for the importance of maximisation-style reasoning, this style of reasoning is simultaneously dangerous and liable to fanaticism. The only real solution to this problem is a proper understanding of the context and limits of maximisation. And it is here that Effective Altruism has come up short."

You can read McLaughlin's full post here (~22 minute read).

2—A Nobel for and by central bankers

The 2022 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to former Fed chair Ben Bernanke, along with Douglas Diamond and Philip Dybvig, for "research on banks and financial crises".

Financial crises are bad, so praising the work of economists who have looked into it is surely good, right? Well, not really. In his annual Nobel opinion piece in the WSJ, David Henderson writes that:

"Mr. Bernanke thought providing more liquidity during a crisis wasn't enough; he emphasized the importance of salvaging particular financial intermediaries, even if some of them arguably should have gone bankrupt. While his academic work on this issue was deep and impressive, it unfortunately caused him, as Fed chairman, not to focus on liquidity during the financial crisis.

...

Had Mr. Bernanke simply increased the money supply substantially, as Alan Greenspan had done in response to the 1987 market crash, the 2007-09 recession would have been shorter and shallower. The second measure restraining liquidity was Mr. Bernanke's 2008 choice to pay interest on bank reserves, which caused banks to sit on reserves rather than lend them out."

When you spend your life studying a specific crisis, you can fall into the trap of seeing all crises through that lens. Put that person at the head of the Fed and they can do some serious damage. Henderson continues:

"As for Messrs. Diamond and Dybvig, their 1983 model purports to give a theoretical explanation of how bank runs occur, but what it calls 'banks' are like no banks we know of... [but instead] imagines an economy with a single bank that doesn't make loans and doesn't issue checking accounts. The reason for bank runs, according to the model, is that investors (not account holders, since there are none) get nervous and try to cash in their investments. The Diamond/Dybvig model uses this bank-run potential to justify deposit insurance."

You can read Henderson's full article here (~4 minute read), which goes on to list better ways to avoid bank runs without deposit insurance (and the negative incentives it creates), concluding that "The 2022 award seems to be an affirmation by central bankers [the prize is awarded by the Swedish central bank] of the value of central banking."

3—Already in recession

4—No one really knows what they are doing

How will European countries wriggle their way out of the Russia-induced energy shock that could run as high as 8% of their collective GDP? According to Tyler Cowen, their governments have a few options:

"One response to this shock would be to let energy prices rise and allow the private sector to adjust. This would mean higher costs for manufacturing, higher home heating bills, and lower disposable income to spend on other goods and services."

That's probably the sensible option, so it's unlikely to be followed by European politicians. Cowen goes on to name "a different yet equally grim path":

"If a government picked up the entire extra energy cost, it would cost something in the range of 6% to 8% of GDP — and that cost would need to be incurred every year that energy prices stayed high. That would require more government borrowing, higher taxes, more money printing, or some mix of those options.

The good news is that turning an energy crisis into a fiscal crisis doesn’t spread high energy costs through the entire economy. The bad news is twofold: First, keeping energy prices low does nothing to encourage conservation. Second, and more important, a fiscal crisis is still a crisis. Even if a government eschews extra borrowing, how much room is there to raise taxes, given economic and political constraints?"

You can read Cowen's full article here (~3 minute read), in which he notes that the UK and German governments have already at least partially adopted the second option. But Cowen is left wondering, with government debt already at record levels, "for how long can the world fiscalise its problems?"

5—Further reading...

🚢 From twitter: "After maxing out at 22% in 2017, China's share of US goods imports has fallen to 17%. No evidence of reshoring: US import value grew 21% from 2017-2021 compared with 4% from 2013-2017. Nor nearshoring: Rest of Asia absorbed the drop, with Asia's share of US imports flat at ~45%."

🏦 Larry Summers: "Outside of the security domain, overhauling the World Bank offers US President Joe Biden’s administration its greatest opportunity for a key foreign-policy achievement. The World Bank should be a major vehicle for crisis response, post-conflict reconstruction, and, most importantly, for supporting the huge investments necessary for sustainable and healthy global development. But currently it is not."

😷 China's dynamic zero-COVID: "Cases are rising again, new Omicron variants have entered the country, Shanghai is seeing more targeted lockdowns, and official media are making clear dynamic zero-Covid is the correct policy and is not going away. I don’t have any other word to describe the situation other than grim."

📉 According to Deutsche Bank: "It is reasonable to say that a crisis [in emerging markets] has already arrived. While most of the stress so far has been in frontier markets, the pressure has been broad-based and felt in both offshore and local currency markets." Sri Lanka and 14 countries have seen their access to international credit "virtually shut off".