Building castles in the sky

1—Building castles in the sky

What is the metaverse and does it even matter? It turns out that no one really knows what 'metaverse' means:

"This word has become so vague and broad that you cannot really know for sure what the speaker has in mind when they say it, since they might be thinking of a lot of different things. Neal Stephenson coined the word but he no longer owns it, and there's no Académie Française that can act as the tech buzzword police and give an official definition. Instead 'metaverse' has taken on a life of its own, absorbing so many different concepts that I think the word is now pretty much meaningless - it conveys no meaning, and you have to ask, 'well, what specifically are you asking about?'

...

Sometimes 'metaverse' can feel like a catalogue of everything and anything cool that might happen in tech in the next decade - which, again, makes it hard to know what anyone saying it has in mind, if indeed they care."

That's from Benedict Evans, who says part of the confusion when talking about the metaverse is the word 'the':

"...which leads many people to talk as though this will be a completely separate thing unrelated to the internet, and to ask absurd questions like 'does France need its own metaverse?' or 'will there be more crime on the metaverse?' It's useful to try replacing 'the metaverse' with 'mobile' or 'apps' to see whether such questions make any sense."

As to whether the metaverse will ever actually amount to anything:

"We can't know the answer to this. A lot of very clever people did not realise that mobile would replace PCs as the centre of tech (indeed, some people still don't understand that's happened), so check back in a decade to find out. But the test is that for VR and AR to matter, we need to do things where 3D matters, whereas mobile did not have to create mobile things.

...

"Going back to the mobile internet in 2002, many of us knew that this would be big, almost no-one thought it would replace PCs, and only a crazy person would have said that the telcos, Nokia and Microsoft would play no role at all and a had-been PC company in Cupertino and a weird little 'search engine' would build the new platforms. So be careful building castles in the sky."

You can read the full article from Benedict Evans here (~11 minute read).

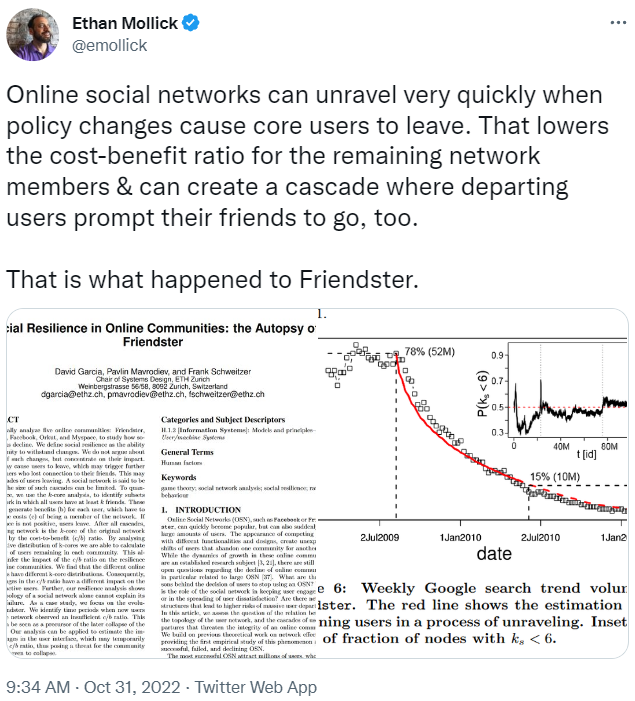

2—Is Meta dying?

Meta's share price has fallen a staggering 75% since September 2021, taking the Facebook owner's inflation-adjusted valuation all the way back to where it was in 2014. But does that mean Facebook is dying? Not according to Ben Thompson:

"The problem is that the evidence just doesn't support this point of view. Forget five lenses: there are five myths about Meta's business that I suspect are driving this extreme reaction; all of them have a grain of truth, so they feel correct, but the truth is, if not 100% good news, much better than most of those dancing on the company’s apparent grave seem to realise."

Thompson points out that Meta is still adding users; competition from TikTok is "depressing growth, not in reversing it"; TikTok usage is also plateauing; Apple's privacy features "lopped off a big chunk of revenue" but digital advertising is still growing strongly; and Meta's large non-metaverse capital expenditure is being spent well, by building probabilistic models (AI) aimed at countering TikTok and Apple's privacy controls.

You can read Thompson's full article here (~14 minute read), which concludes that while Meta's metaverse investment might be "bad business... the old Facebook is still a massive business with far more of its indicators pointing up-and-to-the-right than its Myspace-analogizers want to admit".

3—Consumer sovereignty

4—Pretty poor for a rich place

How has the UK fallen so far behind its Western European peers? Decades of "economic dysfunction":

"Under Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s, markets were deregulated, unions were smashed, and the financial sector emerged as a jewel of the British economy. Thatcher's injection of neoliberalism had many complicated knock-on effects, but from the 1990s into the 2000s, the British economy roared ahead, with London's financial boom leading the way. Britain, which got rich as the world's factory in the 19th century, had become the world's banker by the 21st.

When the global financial crisis hit in 2008, it hit hard, smashing the engine of Britain’s economic ascent. Wary of rising deficits, the British government pursued a policy of austerity, fretting about debt rather than productivity or aggregate demand. The results were disastrous. Real wages fell for six straight years. Facing what the writer Fintan O'Toole called 'the dull anxiety of declining living standards,' conservative pols sniffed out a bogeyman to blame for this slow-motion catastrophe. They served up to anxious voters a menu of scary outsiders: bureaucrats in Brussels, immigrants, asylum seekers—anybody but the actual decision makers who had kneecapped British competitiveness."

That's from Derek Thompson, who pinpoints the blame at Britain's government and British voters, who "chose a closed and poorer economy over an open and richer one".

Interestingly, the media's obsession about robots and AI putting people out of work turned out to be completely unfounded, with the reality "closer to the opposite":

"Between 2003 and 2018, the number of automatic-roller car washes (that is, robots washing your car) declined by 50 percent, while the number of hand car washes (that is, men with buckets) increased by 50 percent. It's more like the people are taking the robots' jobs.

That might sound like a quirky example, because the British economy is obviously more complex than blokes rubbing cars with soap. But it's an illustrative case. According to the International Federation of Robotics, the U.K. manufacturing industry has less technological automation than just about any other similarly rich country. With barely 100 installed robots per 10,000 manufacturing workers in 2020, its average robot density was below that of Slovenia and Slovakia. One analysis of the U.K.'s infamous 'productivity puzzle' concluded that outside of London and finance, almost every British sector has lower productivity than its Western European peers."

You can read the full story here (~5 minute read), which laments that "the UK, the first nation to industrialise, was also the first to deindustrialise", and is "trapped between a left-wing aversion to growth and a right-wing aversion to openness".

5—Further reading...

⌚ Scientists discovered a new way of measuring time "in the very shape of the quantum fog itself".

🚘 Ford abandoned its $US4 billion investment into self-driving developer Argo, "just the latest sign that the global effort to get cars to drive themselves is in trouble—or at least more complex than once thought".

📉 "Only 22 or less than 1 per cent of 2,296 [Chinese] equity mutual funds managed to stay above water this year through October, according to data East Money."

🔐 "In Foxconn's main Zhengzhou facility, the world's biggest assembly site for Apple Inc.'s iPhones, hundreds of thousands of workers have been placed under a closed-loop system for almost two weeks. They are largely shut off from the outside world, allowed only to move between their dorms or homes and the production lines."

🌽 "Russia says it's suspending its participation in the grain deal... after it accused Ukraine of attacking the Russian Black Sea fleet."